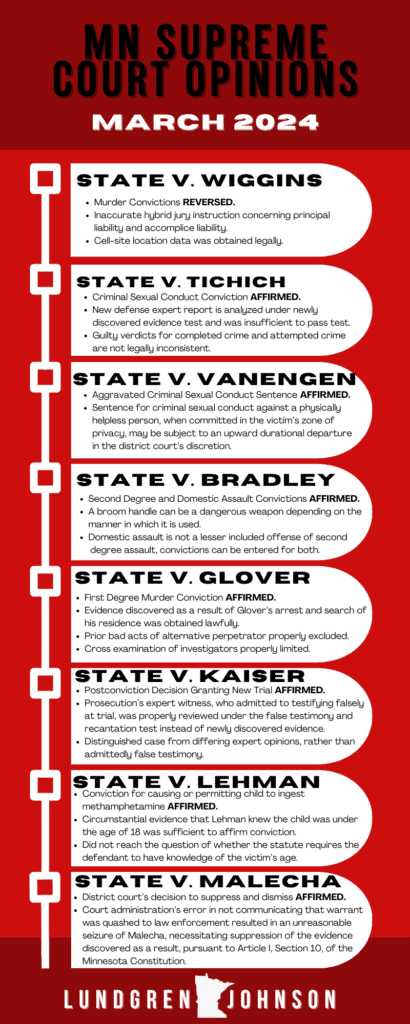

Criminal defense lawyer David R. Lundgren summarizes the criminal legal opinions published by the Minnesota Supreme Court in March 2024 in the video below. The following opinions are summarized: State of Minnesota vs. Wiggins, State of Minnesota vs. Tichich, State of Minnesota vs. Vanengen, State of Minnesota vs. Bradley, State of Minnesota vs. Glover, State of Minnesota vs. Kaiser, State of Minnesota vs. Lehman, and State of Minnesota vs. Malecha.

Transcript for “Minnesota Supreme Court Criminal Opinions Analysis | March 2024”

Hello, my name is David Lundgren, I am a criminal defense lawyer located in Minneapolis. I wanted to take some time today to provide a digest and a brief summary of the Minnesota Supreme Court’s criminal opinions for the month of March, 2024.

The goal of these summaries is to be specific enough to be of assistance to legal practitioners in identifying the legal issues raised and decided, while being broad enough for non-legal professionals to understand the nature of the cases and emerging legal issues.

It was a busy month of March for criminal cases decided at the Minnesota Supreme Court. The Court issued opinions in nice criminal cases. I’ll briefly summarize the issues in each and the court’s decisions for those matters.

In State vs. Wiggins, the court considered two issues in Wiggins’ appeal from his conviction for first degree premeditated murder, attempted first degree premeditated murder, first degree intentional murder while committing a felony, and kidnapping.

The first issue was whether the State legally obtained his cell-site location information. For those of you who don’t know, cell-site location information is location information that can be obtained from an individual’s cell phone provider by determining what cell phone tower, or towers, their phone was being routed through at given periods of time. Wiggins argued that the cell-site location information was obtained illegally because the warrant that was used lacked probable cause. Wiggins argued that the informants referenced in the application for the search warrant were not reliable and that the warrant did not establish probable cause that Wiggins was involved in the murders. The court determined that the application did establish the informants’ reliability and the application as a whole established probable cause that Wiggins was involved in criminal activity connected to the murder, and that evidence linking him to the crime would be found in the cell-site location information held by his cell phone provider.

The second issue was whether the district court committed reversible error when it provided instructions to the jury on accomplice liability. The Supreme Court found that the district court did commit reversible error because the district court provided the jury a hybrid instruction that included both principal liability and accomplice liability within the same instruction. In so deciding, the Minnesota Supreme Court found that the hybrid jury instruction allowed the jury to convict Wiggins under the theory of accomplice liability without finding that he intentionally aided another person, which is a requirement for accomplice liability. Relying on prior precedent, the Minnesota Supreme Court reiterated the dangers that hybrid instructions pose in that regard, and stated that they should no longer be utilized. The Supreme Court reversed Wiggins convictions and remanded the matter to the district court for further proceedings, likely a retrial.

Moving on to the Court’s next opinion, in State v. Tichich, the Minnesota Supreme Court considered two issues in Tichich’s appeal from third degree criminal sexual conduct and attempted third degree criminal sexual conduct guilty verdicts.

The first issue in Tichich was whether a defense expert witness opinion on DNA evidence that was obtained after his trial and conviction could establish that the State’s expert witness testimony on that topic was false.

The Supreme Court determined that a defendant that only offers a new expert witness opinion that differs from a prosecution expert witness’s opinion does not establish that the State’s expert witness testimony was false. The court likened this testimony to the proverbial “battle of the experts,” that is, it is fairly common for experts who are learned on a given topic to disagree with one another. That difference of opinion does not render the other expert’s opinion to be false. Instead, the Supreme Court concluded that the new expert defense witness’s opinion is better analyzed under the newly discovered evidence doctrine. In that regard, the Supreme Court found that the newly obtained expert witness opinion failed the third and fourth prongs of the newly discovered evidence test because the new evidence only served to impeach evidence admitted at trial and the new evidence probably would not have produced an acquittal or other favorable result at trial.

The second issue in Tichich was whether guilty verdicts for a completed crime and an attempted crime for the same conduct are legally inconsistent. The court decided that convictions were not legally inconsistent because noncompletion of the underlying crime is not a necessary element of attempt. The Supreme Court noted that just because guilty verdicts can legally be returned for both an attempt and a completed crime, it does not mean that a defendant can be convicted of both offenses because of a separate legal doctrine that prohibits duplicative convictions for the same conduct.

For the next opinion, the Minnesota Supreme Court decided in State vs. Vanengen that an upward durational departure is legally permissible for convictions of criminal sexual conduct against a physically helpless person when the offense occurred within the victim’s zone of privacy. In that case, Vanengen argued that because criminal sexual conduct against a physically helpless person typically occurs within the victim’s zone of privacy, he should not have received an aggravated sentence. However, the Minnesota Supreme Court disagreed with Vanengen’s assertion that sexual assaults of physically helpless persons typically occur within the victim’s zone of privacy. Moreover, the Supreme Court determined that Vanengen’s assertion, even if it were true, was immaterial. The Supreme Court explained that an aggravated departure for crimes that occur within the victim’s zone of privacy are premised on the notion that the psychological harm on the victim is more pernicious under those circumstances, irrespective of whether such crimes typically occur within a victim’s zone of privacy or not. Vanengen’s sentence was affirmed by the Minnesota Supreme Court.

Moving on to the Court’s next opinion, in State v. Bradley the Supreme Court decided two issues in affirming Bradley’s convictions for second degree assault and domestic assault.

First, Bradley argued that there was insufficient evidence for his second degree assault conviction. Specifically, he argued that a broom handle did not meet the definition of a dangerous weapon which is an essential element of second degree assault. The Minnesota Supreme Court disagreed, and found that the manner in which the broom handle was used was likely to produce great bodily harm. In so finding, the court explained, 1) the broom handle was 2- to 3-foot-long and an inch in diameter; 2) Bradley was in an argument with the victim when he struck her with the broom handle; 3) Bradley swung at and hit the victim’s head, a particularly vulnerable part of the body; 4) while attacking; 5) which caused a gash requiring transportation to the hospital by ambulance for medical treatment including seven stitches; and 6) caused the broom handle to break. Therefore, there was sufficient evidence for Bradley’s second degree assault conviction.

Second, Bradley argued that Minnesota’s statutory prohibition for convictions related to lesser degrees of the same crime prohibit his convictions for both second degree assault and domestic assault. The Minnesota Supreme Court decided that domestic assault is not a lesser degree of second degree assault because domestic assault is codified in a separate portion of Minnesota’s statutes and is not part of the multi-tier statutory scheme for assault in the first through fifth degrees. Because domestic assault is not part of the ordinal statutory scheme for general assaults such as second degree assault, a person can be convicted of both offenses even when the crimes occurred as part of the same behavioral incident. The Minnesota Supreme Court also noted that just because a person can be convicted of both offenses, does not mean they can receive punishments for both offenses, because that is governed by a separate legal doctrine that prohibits multiple punishments for a single behavioral incident.

For the next opinion, the Minnesota Supreme Court decided four issues in State vs. Glover. Glover appealed his conviction for first degree murder while committing a drive-by shooting. Glover raised four issues with the trial below.

First, he contended that the district court erred when it decided that he was legally arrested and therefore the evidence that was discovered as a result of his arrest was admissible at trial. The Supreme Court found that the objective evidence underlying the decision to arrest Glover, available to police at the time of his arrest, established probable cause. That evidence included security footage depicting the following: Glover and the victim having an animated exchange on the bar’s patio; Glover monitoring the victim inside the bar; Glover going outside to an idling vehicle and reaching inside; Glover climbing into his car across the street from the bar and turning off the headlights; a third party walking outside with the victim towards Glover’s car and rounding the passenger side; the victim collapsing in the street near Glover’s driver’s side window after being shot 10 times; and Glover’s car speeding away immediately after the shooting.

Second, Glover contended that the search warrant for his home was invalid and the evidence discovered as a result should be suppressed because the police made factual misrepresentation in the search warrant application. Glover contended that the statement that he was involved in a confrontation with the victim prior to the shooting was a misrepresentation. The Supreme Court reviewed the surveillance video of the incident and determined law enforcement’s characterization of it as a confrontation was not a reckless misrepresentation, and therefore, the warrant was validly issued.

Third, Glover argued that the district court erred when it allowed him to present an alternative perpetrator theory of defense while simultaneously denying him the opportunity to admit certain prior bad acts of the alternative perpetrator. Glover moved the district court to admit two prior criminal convictions of the alternative perpetrator, a threats of violence incident and aggravated robbery incident. The Minnesota Supreme Court determined that the district court did not commit error when it excluded that evidence from trial because the prior incidents were not sufficiently similar in terms of time, place, or modus operandi. The following dissimilarities between the prior incidents and the murder in this case persuaded the Minnesota Supreme Court that the district court reached the right conclusion: neither of the prior incidents involved a shooting or a death and the incidents occurred years before the murder, not days or weeks.

Fourth, Glover contended that the district court erred when it prohibited him from cross examining investigators about a prior shooting involving the victim. Glover wished to demonstrate that the police overlooked a possible lead because the victim in the case had been a prior victim of an unsolved shooting. However, the Minnesota Supreme Court determined Glover failed to identify a suspect for the prior shooting and failed to identify any reason why the investigators should have believed the prior shooting was connected to the murder.

Glover’s conviction was affirmed by the Minnesota Supreme Court.

Moving on to the next opinion, in State vs. Kaiser, the Minnesota Supreme Court affirmed the district court’s decision to grant Kaiser a new trial following his convictions for second degree felony murder.

At issue in Kaiser was the false testimony of a State’s expert witness. Unlike the situation in Tichich, the testimony of the prosecution’s expert witness at trial was false according to the very same expert, as opposed to a differing opinion from another expert. At trial, the prosecution’s expert testified that the injuries observed in the decedent could only be explained by an assaultive trauma, as opposed to some other natural cause. At a postconviction hearing, that same expert admitted that there could have been many other causes for the type of injury at issue and that his prior testimony to the contrary would have been incorrect.

The Minnesota Supreme Court agreed with the district court’s application of the false testimony and recantation test as opposed to the newly discovered evidence test. It found that the expert’s prior testimony was false, that the jury may have reached a different conclusion at trial without the false testimony, and that Kaiser was taken by surprise by the false testimony at trial. Accordingly, the Court affirmed the district court’s decision to grant Kaiser a new trial.

In reaching their decision, the Minnesota Supreme Court acknowledged the narrowness of its holding and applicability of the decision to future cases. The Court specifically identified that applying the false testimony and recantation test to expert witness testimony is only appropriate in situations where expert testimony is stated as a medical fact, and that the testimony is objectively false. It is not to be applied where there’s simply a disagreement by experts in the field at issue. That situation is more akin to the Court’s decision in Tichich.

For the next opinion, in State vs. Lehman, the Minnesota Supreme Court affirmed Lehman’s conviction for causing or permitting a child to ingest methamphetamine. In that case, Lehman argued that he could not be convicted for the crime because the statute required that he have knowledge that the child was under the age of 18 and the State did not present any evidence at trial on that point. The court of appeals decided that the statute did not require such knowledge for a person to be convicted. The Minnesota Supreme Court accepted review, and affirmed the conviction on alternative grounds. The Minnesota Supreme Court did not reach the issue of whether the statute requires knowledge of the victim’s age. Instead, the Supreme Court explained that the evidence presented at trial, including Lehman’s extensive and lengthy contact with the child’s family and Lehman’s weekly contact with the child, was sufficient evidence of Lehman’s knowledge that the child was under the age of 18.

For the last opinion, in State v. Malecha, the Minnesota Supreme Court decided an important issue on the extent of the protections of Article I, Section 10, of the Minnesota Constitution. Article I, Section 10, is Minnesota’s corollary to the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In this case, Malecha encountered law enforcement and they believed she had an active warrant for failing to appear in court. In reality, there was an active warrant, but it should have been recalled by court administration pursuant to a prior judicial order quashing the warrant. Because the records had not been transmitted appropriately by court administration, the police apprehended Malecha on the warrant, found suspected controlled substances, and she was charged for possessing them. The district court suppressed the evidence due to the warrant being invalid at the time, but the court of appeals reversed the district court. The Minnesota Supreme Court reversed the court of appeals, thereby affirming the district court’s dismissal. In doing so, the Minnesota Supreme Court extended Minnesotan’s protections against unreasonable searches and seizure under the Minnesota Constitution, beyond what is provided for by the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitutions. The Minnesota Supreme Court found that court administration’s error in not conveying that the warrant was quashed to law enforcement resulted in an illegal search and seizure under Minnesota’s constitution. Further, the Minnesota Supreme Court decided that the good faith exception to the exclusionary rule did not apply. The Minnesota Supreme Court determined that applying the exclusionary rule to these circumstances served the purpose of deterring unlawful government conduct, deter clerical errors, and incentivize accurate record keeping and updating of computer records. The Supreme Court decided that applying the exclusionary rule here establishes that court employees, not only law enforcement officers, are held to account for errors that result in constitutional violations. Further, imposing the sanction of exclusion in this case promotes the public perception of fairness in the judicial process, particularly as illegally obtained evidence would otherwise be admitted by the same court system whose personnel caused the error that led to the unlawful search or seizure.

Thanks for taking the time to listen to this summary of the legal opinions issued by the Minnesota Supreme Court in March of 2024. I hope this helped and informed you in some way. If you have any questions, please feel free to reach out. I am happy to be a resource whenever possible. Take care.